|

October 5, 2011 - In the

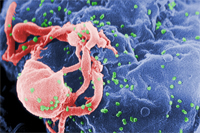

mid-1990s, the widespread introduction of modern antiretroviral therapies changed

a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

infection from a rapid death sentence to a chronic condition that could be managed over decades. But as the first generation

of patients receiving these therapies enters late middle age, new challenges are appearing, including a dramatic increase

in the incidence of cancers that were not traditionally viewed as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated

malignancies. October 5, 2011 - In the

mid-1990s, the widespread introduction of modern antiretroviral therapies changed

a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

infection from a rapid death sentence to a chronic condition that could be managed over decades. But as the first generation

of patients receiving these therapies enters late middle age, new challenges are appearing, including a dramatic increase

in the incidence of cancers that were not traditionally viewed as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated

malignancies.

Several types of cancer were seen frequently in the early years of the AIDS epidemic; three

types- Kaposi sarcoma , non-Hodgkin lymphoma , and

cervical cancer -are called the "AIDS-defining cancers." A diagnosis of

one of these three cancers can mark the point where HIV infection has progressed to full-blown AIDS.

Researchers tracking the relationship between HIV and cancer over the decades have noticed a substantial

shift in cancer epidemiology in HIV/AIDS patients. In

April of this year, investigators from NCI's Division of Cancer Epidemiology

and Genetics (DCEG) reported in the

Journal of the National Cancer Institute that from 1991 to 2005, even with a quadrupling of the HIV-positive population

in the United States, the number of AIDS-defining cancers diagnosed in that population had fallen by more than two-thirds.

In contrast, the number of non-AIDS-defining cancers had tripled, with the highest number of these new cases

coming from anal , liver , prostate , and

lung cancers and Hodgkin lymphoma . "A big part

of it is that patients with HIV are getting older, and many types of cancer just become more common as people age," said Dr. Eric Engels,

senior author of the DCEG study.

"The HIV-positive population also has a lot of other risk factors for cancer, and that's also contributing," he

added. These risk factors include co-infection with other cancer-causing viruses such as the human papillomavirus (HPV,

which causes cervical, anal, oropharyngeal , and other cancers)

and the hepatitis C virus (HCV, which causes liver cancer),

a high rate of smoking, and possibly the long-term effects of HIV itself on the immune system.

Clinical Trials Conundrum

The increase in HIV-positive patients requiring treatment for non-AIDS-defining malignancies presents a new conundrum: how to provide

the best and safest treatments when data from clinical trials are lacking for these patients. "Traditionally, HIV-positive

patients were de facto excluded from NCI-sponsored clinical trials, except those targeted to AIDS-defining malignancies

like Kaposi sarcoma," said Dr. Robert Yarchoan, director of NCI's Office of HIV and AIDS Malignancy (OHAM).

This exclusion was not based on discrimination, but rather reflected AIDS patients' high susceptibility to drug toxicity, resulting from their profound immunodeficiency.

Also, because they were at risk of death from AIDS, they would confound survival results, Dr. Yarchoan explained.

These concerns are now being reevaluated. The development of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART, also known as

combination antiretroviral therapy) has converted HIV infection to a chronic, manageable disease in most cases, and such patients can

now better tolerate chemotherapy. However, a lingering concern is the potential for unknown pharmacokinetic interactions

between the antiviral treatments used to keep HIV under control and cancer chemotherapy drugs or newer biological therapies.

Five years ago, to address the changing pattern of cancers in HIV-infected patients, the NCI-sponsored AIDS Malignancy Consortium (AMC, which spun

off from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases' AIDS Clinical Trials Group in 1995) created

a new working group on non-AIDS-defining cancers. "We felt [cancer] was becoming a bigger part of the AIDS epidemic, and we needed

to have a way of testing new drugs in these cancers," said Dr. Ronald Mitsuyasu, director of the AMC and the Center for Clinical

AIDS Research and Education at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The consortium has finished its first safety trial, looking at sunitinib in HIV-positive

patients whose cancers have not responded to standard treatments. It has other such trials in development, testing a variety of newer

treatments including vorinostat , erlotinib , and

other targeted drugs. "Once we've defined that we can safely give a drug and how to give it, any NCI-sponsored trials of these drugs

that excludes patients with HIV will be amended to allow individuals with HIV to enroll, assuming there's no other medical reason they

shouldn't participate," explained Dr. Richard Little, who leads HIV research in NCI's Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) .

"We're trying to make physicians more comfortable with enrolling HIV patients in general oncology trials, so that [HIV status] won't be an automatic exclusion in the

future," said Dr. Mitsuyasu. "Patients with HIV need access to these trials just as much as anyone else does."

In a related effort, CTEP has funded the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network to perform

two clinical trials in HIV-positive patients, one of autologous bone marrow transplantation,

and one of allogeneic transplantation . "Assuming that

these studies indicate that it is feasible and safe to transplant HIV-positive patients for their underlying cancer, trials that

currently exclude them based on concerns that this is not safe would be amended," explained Dr. Little.

Once we've defined that we can safely give a drug and how to give it, any NCI-sponsored trials of these drugs that exclude patients with HIV will be amended to allow individuals with HIV to enroll, assuming there's no other medical reason they shouldn't participate.

-Dr. Richard Little

"I think the culture is actually changing as people are thinking more appropriately about why patients with

HIV should be included or excluded," he continued. "We're trying to create a culture where the first idea is, yes,

they should be included on a trial unless there's a specific reason that would make that unsafe. People in the research

community are being very responsive to that way of approaching patients."

Increasing Visibility

In the early days of the AIDS epidemic, patients with HIV changed the clinical trials process in the United States, demanding rapid

access to investigational drugs and encouraging community participation. Today, "people don't volunteer like they

used to," said Dr. James Weihe, a psychiatrist who worked on the first AIDS unit at San Francisco General

Hospital back in the early 1980s and now works as an advocate and community representative for the AMC.

"You saw all your friends dying around you, so people were motivated" to participate in clinical trials, he

remembered. "In 1988, you walked down the street in San Francisco and you saw people with Kaposi sarcoma, you saw young people

using canes and walkers and wheelchairs. You don't see that anymore-people look healthy, and the disease has become more invisible."

In addition, even though non-AIDS-defining cancers are becoming more common in people with HIV, "cancer is still

relatively rare-people don't know about [the risk], and they don't necessarily talk to each other about cancer, like they would

for antiviral trials," he continued.

Since most people are referred to cancer clinical trials by their doctors, Dr. Weihe believes it is important to raise

awareness among doctors about cancer trials for HIV-positive patients. "A lot of people don't even know the AMC exists," and

outside big cities and academic centers, "a lot of doctors aren't going to have a large HIV caseload. It's especially important

for us to work with community physicians, because that's where most patients are going."

Drs. Weihe and Mitsuyasu are excited about a new cancer prevention trial the AMC hopes to launch, which will look at

whether anoscopy (an examination of the anal canal) and removal of abnormal tissue can prevent progression to anal cancer, similar

to how the Pap smear and treatment of early

cervical lesions can prevent the

development of cervical cancer. (Both of those cancers are caused by HPV.) "I think the community

might get more involved in this sort of trial-trying to prevent cancer," said Dr. Weihe.

The shift from people with HIV getting cancers at an early age to them getting other cancers at a later age is evidence

of the public health benefit of better treatments for HIV, concluded Dr. Yarchoan. "Instead of people dying of lymphoma (or AIDS)

at the age of 30, they might possibly get lung cancer at the age of 55 or 60. They have many more years without cancer, if they

develop it at all. That's a real development that sometimes gets lost in the story," he said.

- Sharon Reynolds

###

Source: National Cancer Institute

http://www.cancer.gov/ncicancerbulletin/100411/page7

|